Simon Champ: Artist and Mental Health Activist

Simon Champ (b. 1957) is a pioneering consumer activist who has advocated for the rights of individuals with mental illness in Australia since the early 1980s. He has been active in fighting the stigmas associated with mental illness, motivated by the conviction that individuals experiencing mental distress are individuals like everybody else and that they should be recognised as such.

Simon first experienced mental distress during the HSC in high school and had to repeat a year. He lived in a country town some ‘300 miles from Adelaide and 300 miles from Melbourne.’[1] Because his parents did not want to send him far away for psychiatric treatment, he ‘bumbled along and kept having weird experiences.’

Fish Lighthouse. Drawing by Simon Champ.

From an early age, Simon knew he wanted to become an artist. He enrolled in Art School in Adelaide but, in 1981, decided to move to Sydney. On the way, he stayed at the share-farm of a lecturer in photography at Nimbin. He remembers picking mangoes from a large mango tree and went with ‘a lot of mangoes into town and exchanged them for peanut butter.’

Over time, Simon had increasingly unusual and at times imaginative ideas. At one time, he took his guitar and a ghetto blaster, and ‘put it on the edge of the platform near the Opera House and I put the headphones into the water and the dolphins were going to swim into it.’ He was promptly taken to Rozelle Hospital by the police. There, he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia.

In 1981, Simon became a resident of the first house the Richmond Fellowship of NSW had established—in Glebe. He fondly remembers his time there. He remembered when all residents would go out:

When we all went to the local pub, there were more of us than the sane people.

Being in the house was inspiring:

I saw a lot people get well, or find a way of managing their illnesses.

Unfortunately, some residents suicided, which was really difficult to come to terms with. The house was run as a therapeutic community, and everybody had a role to play:

That’s where my pride, prior to being crazy, my recovery of self, began. In those situations where we’d all be together.

Simon was later employed at the house for one night a week, probably as the first peer worker in Australia. Yet Simon never really intended to become a peer worker:

He still wanted to be an artist. In 1985, he enrolled at the Sydney College of the Arts, and joked at the time that he kept his ‘psychosis to the holidays, which was pretty true, actually.’ The Sydney College of the Arts later moved to Callan Park, and many students explored the connections between madness and creativity. Simon gave quite a few talks on this topic and explored this theme during his studies.

While reflecting on the experience of having schizophrenia and his hospitalisation, Champ stated that this condition ‘severely ruptured the relationship that I had enjoyed with myself prior to my illness’.[2]

His treating psychiatrist told him that ‘I could not trust my thoughts and senses. I felt that my mind had betrayed me.’[3]

The medication he received dulled his senses and made his world appear colourless and flat. It was hard to make sense of his own experiences: ‘To try to decide what was normal or sane was like negotiating a foreign city without a map. I felt like a stranger to myself.’[4]

‘My [artistic] work,’ he stated:

became a vehicle for expressing my feelings associated with my diagnosis and helped me rationalise my changed perspective on society. At times in my work, I wanted to try to record and express the effects and unusual mental phenomena that the illness had periodically created within my own mind.[5]

In addition to the effects of schizophrenia, Champ found the experience of hospitalisation deeply troubling.

Through participating in various organisations and by supporting others who had experienced severe mental illness, Simon reports, did he regain his sense of dignity.

In November 1985, Simon attended a public meeting organised by ABC journalist Anne Deveson, whose son had schizophrenia[6], and Margaret Leggett in Sydney.* This meeting was to be the founding event for the Schizophrenia Fellowship of New South Wales.[7] To the surprise of everybody attending, Simon stood up and declared: ‘My name is Simon Champ and I have schizophrenia. I need an organisation like this.’

The new organisation mandated that individuals with a lived experience of schizophrenia were represented at all levels, Simon was soon elected vice-chairman of the board.

That same year, Simon also appeared on the Mike Willesee show, a popular current affairs program at the time, openly discussing what it means to have schizophrenia—both the condition, and the accompanying stigma. Two years earlier, he had appeared on ABC’s Compass, together with Meg Smith, to discuss how both of them lived with mental illness. Openly discussing having a serious mental illness was very unusual at the time, and these appearances on television were important to reduce the stigma surrounding mental disorder.

In 1991, Simon appeared in Anne Deveson’s documentary about schizophrenia (Spinning Out), which was broadcast by the ABC. It had premiered at the Cannes film festival.

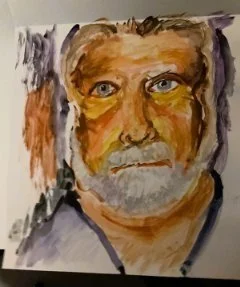

In his art, Simon attempted to convey his experience with mental illness, but also to create a more positive image of schizophrenia.

Painting by Simon Champ. From the Cloud series.

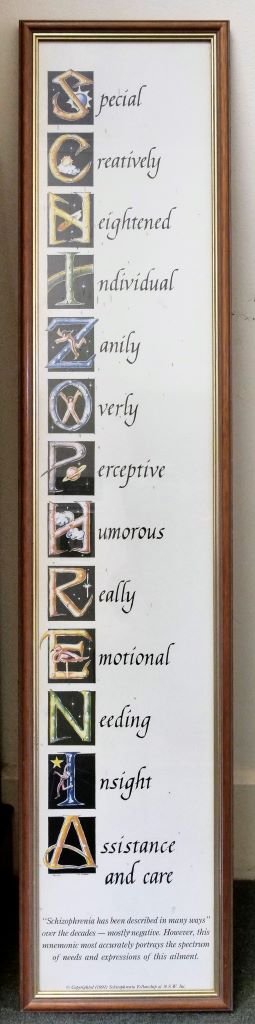

Schizophrenia, by Simon Champ. Courtesy OneDoor Mental Health

He presented a positive mnemonic for schizophrenia as a Special Creatively Heightened Individual Zanily Overly Perceptive Humorous Really Emotional Needing Individual Assistance.

The Schizophrenia Fellowship, in association with the New South Wales Association for Mental Health, organised a program for high school students. Individuals with mental illness visited high schools to discuss their life experiences and public attitudes towards mental illness. Simon visited many high schools; the program was highly effective.

A similar program was undertaken to make the police more familiar with individuals with mental illness, in the hope that this would assist them dealing with individuals with unpredictable and seemingly threatening behaviour. Simon gave many of these talks. When his audience liked his presentation, ‘they all had glasses of beer at the end of the day. And if you’ve done a good job, the circle would break, and you would be able to stand in the circle and that’d be about 30 cops there.’[8]

When Brian Burdekin started to organise hearings for his influential report on Human Rights and Mental Illness (published in 1993), he wanted to make sure that the voices of consumers of mental health services were heard.[9] Both Simon and Merinda Epstein (from Melbourne) flew all over the country to attend meetings where consumers could share their experiences in the mental health system.

Burdekin’s report influenced the first National Mental Health Strategy, which was published in 1993. As part of that, a National Community Advisory Group, consisting of carers and consumers, was to be established. Simon served as an independent member of this group for 5 years. He was also involved in the Australian Mental Health Consumer network, which was founded in 1997.

Through his art, his work though the Schizophrenia Fellowship and other NGOs, and state and national boards representing consumers of mental health care, Simon helped strengthening the voice of consumers and advocated for them having meaningful roles in organisations providing mental health care and in research initiatives on mental health.

By Hans Pols

* Margaret Legget pioneered changes to the types of mental health organisations serving the community in Victoria. We spoke to Dr Leggett at a roundtable event, On Madess: In conversation with Sandy Jeffs and Margaret Leggatt, hosted by Catharine Coleborne for the University of Newcastle’s History Week 2021 (9/9/2021). To watch this this discussion and explore the multtimedia resources the research team has produced, head to the project’s Resources Page.

References

[1] All citations are derived from Simon Champ, ‘Interview,’ interview by Anthony Harris, Tina Kenny and Hans Pols, Oral History Project on the History of Community Mental Health in Australia, 25 Sept, 2020, unless otherwise indicated.

[2] Simon Champ, ‘A Most Precious Thread’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Mental Health Nursing 7, no. 2 (1998): 54.

[3] Champ, ‘Most Precious Thread’, 54.

[4] Champ, ‘Most Precious Thread’, 55.

[5] Simon Champ, ‘The Colour of Dinosaurs and the Flight of a UFO.’ Graduate Diploma Research paper, Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney, 1993.

[6] See Anne Deveson, Tell Me I'm Here: One Family’s Experience of Schizophrenia (Melbourne: Penguin, 1991).

[7] For the Schizophrenia Fellowship see Virginia Macleod, From Seed to Sunflower: A History of the Schizophrenia Fellowship of New South Wales, 1985-2010 (Sydney: Schizophrenia Fellowship of NSW, 2010).

[8] Simon Champ, ‘Interview,’ 31:21.

[9] Brian Burdekin, Report of the National Inquiry into the Human Rights of People with Mental Illness [Burdekin Report]. Canberra: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission, 1993.